I smacked my foot against a table leg this morning and scolded myself: Watch where you’re going! A blood-bead stood below the nail, whose jaundiced color puzzled our grandson, here for the weekend. He asked, “Grandpa, how come you’re gold?”

But he quickly turned his attention to that little globe of blood. Our interest in pain, or so it seems to me, develops early. We may take whatever measures we can to avoid it and yet it intrigues.

I recall, for instance, a hornet’s stinging that child’s older brother a summer ago. The two still speak of the incident now and then. The pains, or rather for the most part griefs, that hold my own attention now tend to be psychological rather than bodily, however hard they often are to identify exactly.

This grandson of ours owns a little plush dog named Oko for whatever reason, and the child loves to say he’s been stolen by what he calls billains. Or sometimes the dog’s simply lost. I know it’s feigned, yet I still wince at his look, precisely, of pain.

Oko’s never gone for long, however, and I rejoice with the boy when he’s found.

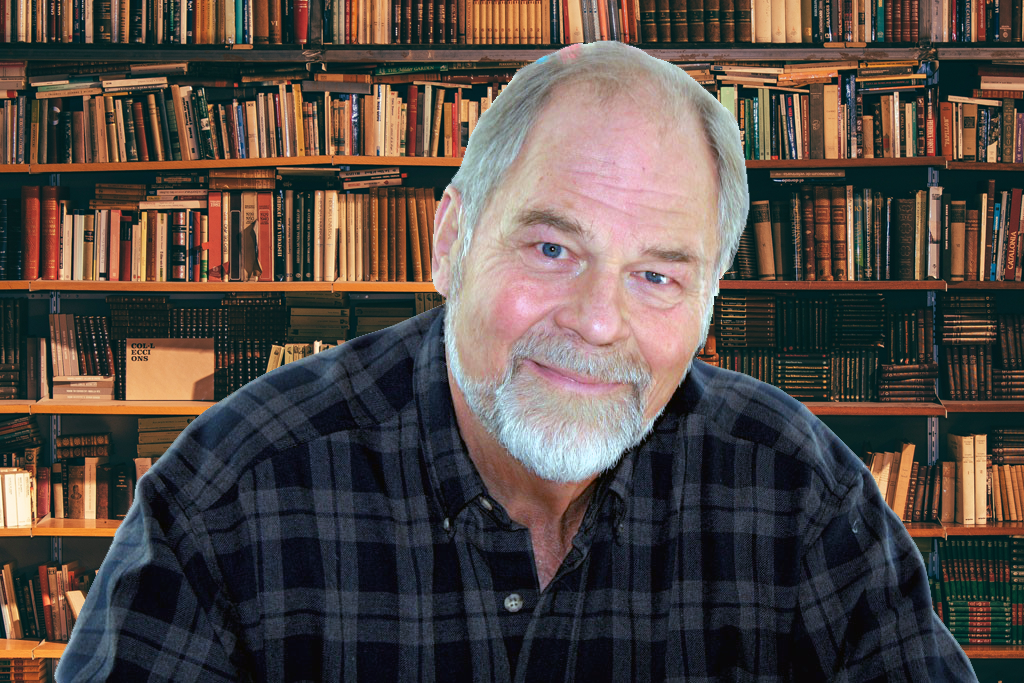

Speaking of loss, at my age I’m losing friends, some to the Reaper, some to scrambled brains. I wish I could find them again, celebrate their return. One of the brightest men I’ve known, for instance, an estimable poet and critic, is now so overwhelmed by multiple sclerosis that he can barely talk, let alone move; another longtime friend, this one Irish, a man with whom I’ve shared woe, delight, and absurdist humor for decades, is in a seaside institution, and doesn’t even know my name; yet another has just been informed that she has incurable stage cancer of the throat, and she’s arranging for hospice care; two springs ago, my very best friend on earth– marathon runner, non-smoker and -drinker– himself contracted irremediable cancer of the duodenum and was gone in less than twelve months. The list seems all but infinitely extensible.

As for me, at last I’ve become my family’s oldest member, apart from two of my own first cousins I haven’t seen in decades. Both my grandparents and parents, one brother, all my aunts and uncles are long since gone. So when Oko disappears and our grandson expects me to make a sorrowful face, I do have resources.

I struggle against dwelling on my own mortality. I don’t always prevail, but when I do arrive at a saner frame of mind, I conclude that so long as I’m not dead, I’m alive. Instead of trying to reckon how long I’ll keep them, I concentrate on my capacious blessings.

Of course, I’m experiencing natural physical decline, but I can still hike, row my shell, and in fact do pretty much what I’ve always done, at however stately a pace. My short-term memory is not what it was, but I can still write and think pretty clearly (at least I think I can). A subtle bittersweetness has taken up permanent residence in my soul, but far better that than dejection

Before we carry him up to bed, our grandson, plush dog in hand, dictates words to us for a postcard we’ll send to his mother and father and that hornet-stung brother.

Grandpa’s toes are gold. Today he bleeded. I lost Oko but Grandpa found him. He’s happy.